Every vessel sailing open seas is required to fly a flag that provides it with legal jurisdiction for its operations in international waters.

Article 91 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) allows flag registries to ‘fix the conditions for the grant of its nationality to ships’ and grant them the right to fly its flag.

These open registries — also known colloquially as flags of convenience — are favoured by shippers due to lower regulatory burdens and registration costs than closed registries, which also require a direct link between the vessel and the nation state.

‘CREA’s new data-rich report evidences not only persistent deficiencies in sanctions enforcement but also the deeper structural weaknesses in international maritime governance that enables shadow fleet operations.’

Gonzalo Saiz Erausquin, Research Fellow, Centre for Finance and Security, Royal United Services Institute (RUSI)

The lower regulatory standards practiced by flags of convenience states have created an increased risk for environmental safety, seafarer safety, sustainable shipbreaking, and provoked questions on their large-scale effect on maritime cargo transport itself. Not coincidentally, a lot of these paradigms also apply to vessels that constitute Russia’s ‘shadow’ fleet, which profit greatly from using open registries to expand their operations and trade. Of the 46 registries that have flagged Russian ‘shadow’ vessels since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, 23 are classified as ‘flags of convenience’ by the International Transport Workers Federation. Vessels flagged by these 23 registries have helped Russia transport EUR 50 bn of Russian crude oil and oil products since their full-scale invasion of Ukraine — accounting for nearly one fifth of all ‘shadow’ fleet cargo.

In 2025 though, following the EU, UK and US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctions on vessels, many open registries have deflagged vessels designated on sanctions lists, and been reluctant to allow new ‘shadow’ vessels to enter their fleet. A reluctance among traditional open registries to offer their services to the ‘shadow’ fleet has seen the proliferation of many new registries with little to no history on maritime transport.

While newer flag registries pose a threat towards sanctions enforcement, the more immediate threat is posed by false flagging operations. A false flag designation is provided by the IMO when ships either register with fraudulent flag states, use a terminated flag registration, or digitally misrepresent their flag to obfuscate their operations.

Operating while flying a false flag effectively voids these vessels’ insurance and classification and leaves them outside the norms of maritime governance — which comes with increased environmental and security risks when they transit territorial waters.

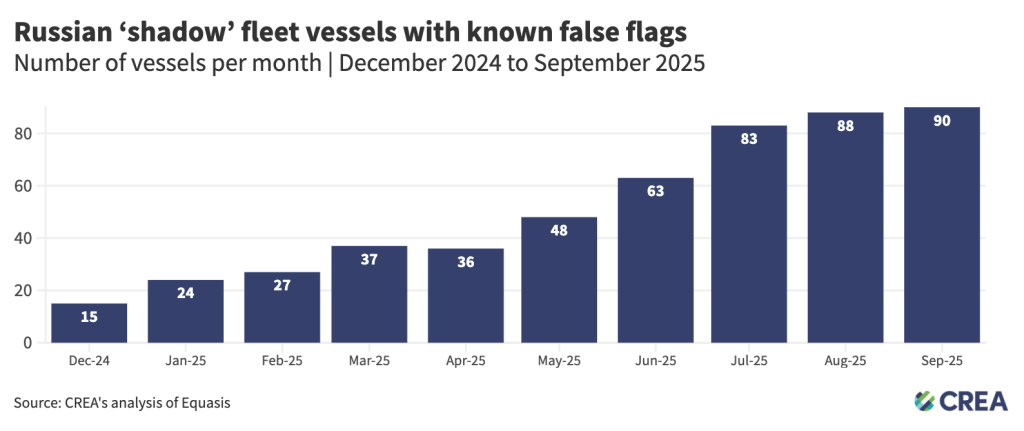

In September 2025, 90 vessels operated under false flags — a six-fold increase from December 2024.

In the first three quarters of 2025, a total of 113 Russian ‘shadow’ vessels have flown a false flag during their operations, transporting thirteen percent of Russian oil — 11 million tonnes, valued at EUR 4.7 bn. This practice poses significant security and environmental risks, undermines global maritime rules, and exploits gaps in flag-state governance.

The most frequently used false flag is that of Malawi. The first such case occurred in June 2025, and since then, 24 vessels have flown Malawi’s flag while carrying Russian oil. Every one of these vessels is sanctioned.

Investigations have found that Malawi’s registry, in reality, does not exist. A purported Marine Services Administration runs the country’s flag registration website and has even established itself as a point of contact in the IMO’s official GSIS database. In July this year, the Malawian Secretary for Transport and Public Works wrote to the IMO asking for ‘appropriate action to be taken against the fraudsters’. Despite this blatant fraud being highlighted by the Malawian authorities the practice has not stopped — in fact, it has only increased.

Key findings:

- In the first three quarters of 2025, a total of 113 Russian ‘shadow’ vessels have flown a false flag during their operations. In volume terms, 13% (11 million tonnes, valued at EUR 4.7 bn) of Russian oil transported by ‘shadow’ vessels between January and September 2025 has been on vessels flying a false flag.

- The insurance of any vessel flying a false flag is void, increasing risk to coastal taxpayers in the event of an oil spill.

- CREA analysis found that there have been 90 vessels which have operated under false flags in September 2025 — a six-fold increase from December 2024. Fifty two of these vessels have traded at least once in the third quarter of 2025.

- False flagging is most common in sanctioned vessels, with 96 vessels under sanctions having flown a false flag at least once till the end of September 2025.

- The false flags of twenty countries have been used by ‘shadow’ vessels. This includes countries which either do not offer flagging services, or have actively denied flagging ‘shadow’ vessels and have deregistered them post sanctions.

- Six flag registries that had not flagged a Russian oil vessel prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine had at least 10 such vessels in their fleet in September 2025. These six registries currently flag a total of 162 ‘shadow’ vessels.

- Of the 46 registries to have flagged Russian ‘shadow’ vessels since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, 23 are classified as ‘flags of convenience’ by the International Transport Workers Federation. These 23 registries have flagged vessels that have transported EUR 50 bn worth of Russian oil since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine — accounting for nearly one-fifth of all Russian oil and oil products transported by the ‘shadow’ fleet.

- A total of 134 vessels sanctioned by the EU, OFAC or the UK till the end of September 2025 have shifted their flag registry once within three months of them being put on sanctions designation lists, showcasing a new market of operators willing to take the risk of providing flag services to these vessels in absence of traditional registries.

- A total of 85 vessels have registered at least two flag changes six months after being sanctioned by the EU, OFAC or UK.

- Recent developments have shown the dangers posed by vessels flying false flags and the inherent risk to maritime regulatory oversight. This provides a unique opportunity for countries to reform flag state regulations and practices at the IMO — chiefly by unifying guidelines for flag states when outsourcing flag services to third country operators.

CREA proposes the following policy recommendations:

- A unified EU database of legitimate flag registries shared between port authorities

- Require flag certification for vessels transiting EU waters

- Expand engagement with and within open registries to tighten net for ‘shadow’ fleet

- Reform existing flag registration norms

- EU coastal maritime enforcement authorities, the UK Maritime and Coastguard Agency and the Royal Navy must detain ‘shadow’ fleet vessels operating under false flags

| Methodology The data used in this analysis is based on CREA’s Russia Fossil fuel tracker methodology. Data for a vessel’s ownership and flag registry records over time was collected from Equasis and cross-referenced with IMO Global Integrated Shipping Information System (GSIS) records. List of ‘shadow’ vessels This CREA analysis uses a compiled list of 590 ‘shadow’ vessels that have transported Russian oil and oil products between 1 January 2024 and 30 September 2025. CREA defines a ‘shadow’ vessel as a vessel that transports Russian oil internationally with no ownership or insurance in sanctioning countries. These ‘shadow’ vessels therefore do not have to comply with the price cap policy. More details on our classification of ‘shadow’ vessels can be found here. |